I learned quickly: membrane thickness quietly skews confining pressure and the curves you trust.

Latex membrane thickness adds radial restraint and tension, shifting effective confining pressure and stress readings; correct choice and simple checks keep values honest.

Here’s the no-drama way to understand and fix it.

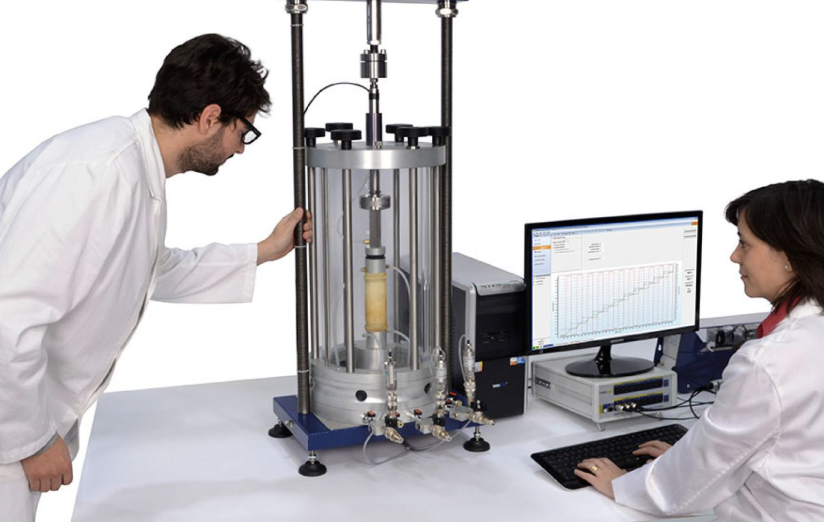

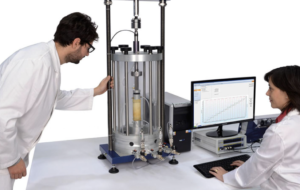

Understanding the Role of Latex Membrane Thickness in Triaxial Testing

The membrane is part of the system, not just packaging. It changes what the specimen “feels.”

Thicker membranes resist radial strain and raise apparent confinement; thinner ones track soil better but risk leaks and wrinkles. Balance, don’t gamble.

When we pressurize the cell, we assume the specimen sees exactly σ₃. Not quite. The latex membrane stretches and carries tension. That tension pushes back against radial expansion, acting like a tiny extra hoop stress. A thicker wall has more stiffness, so the specimen can behave as if σ₃ were slightly higher than the dial says. In clay CU tests, this can raise apparent peak strength and mute dilation; in CD tests, it can smooth out subtle volume-change signals that actually matter for design.

A thin wall keeps this bias small, preserves pore-pressure fidelity, and usually gives cleaner B-values—until you nick it during mounting or it develops micro-wrinkles that fake dilation. So the choice is always contextual: soil D50, angularity, target σ₃, and the test’s main truth (pore pressure vs. volume change).

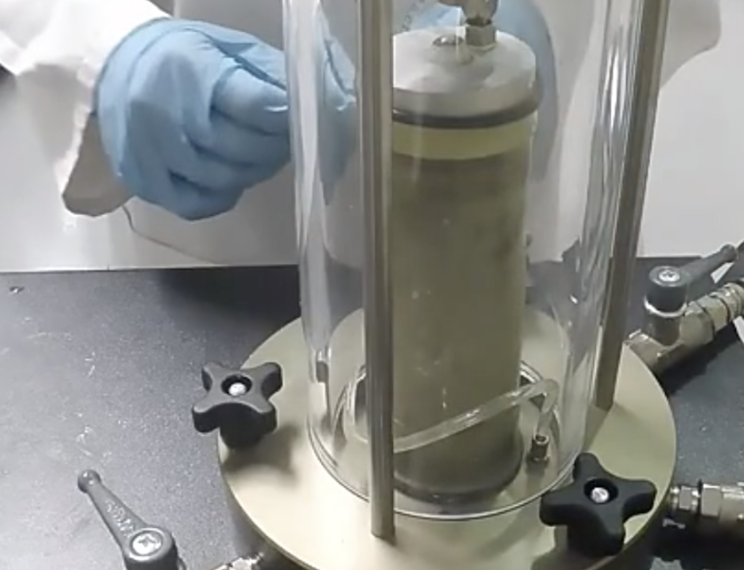

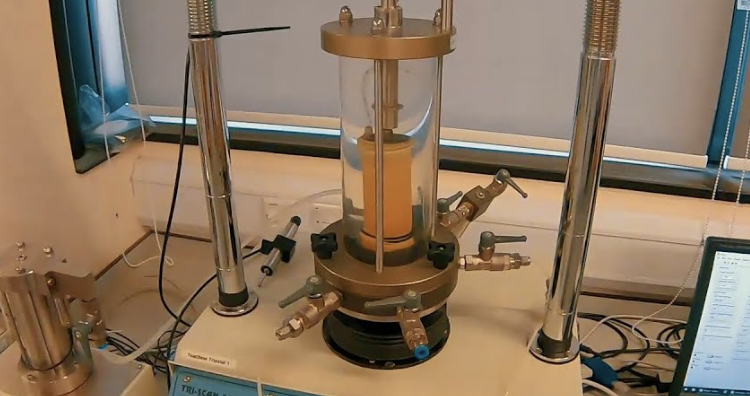

Practical steps help. I run a dummy mount to verify wrinkle-free seating, use transparent membranes when possible to spot bubbles, and keep two thickness grades per diameter—one “thin” for fidelity, one “medium” for durability. Finally, I log thickness with every test; trends in q–ε and u-excess often echo membrane changes. For my quick notes: membrane–system cheat sheet.

The Membrane Penetration Effect and Its Impact on Confining Pressure Accuracy

Under pressure, membranes intrude into particle voids—stealing “volume” and biasing readings.

Penetration makes volume change look larger than reality and can alter the specimen’s effective stress path; use corrections and sizing discipline.

“Membrane penetration” means the wall squeezes into pores between grains when σ₃ rises. In sands and silty sands, this intrusion shows up as an apparent extra compression even when the soil skeleton barely compacts. If you read volume change from burettes or controllers, the curve can look too compressive early on, then “recover” later—classic artifact.

Why it matters for confining pressure accuracy: penetration changes the contact mechanics at the boundary, slightly modifying the way radial stress is transmitted. It also changes how we interpret the σ′ path, because the specimen seems to lose more volume than it truly does. Two fixes help. First, specimen size vs. particle size: keep diameter at least 6–10× D50 so surface porosity doesn’t dominate. Second, thickness choice: a thicker wall can reduce local intrusion but increases hoop restraint; a thinner wall reduces restraint but may penetrate more—so you balance with smoother surfaces, well-seated membranes, and sometimes very light surface sleeves during seating (removed before shearing).

I also apply a small membrane penetration correction for granular materials based on calibration runs with dummy cylinders packed to known void ratios. It’s not perfect, but it stops me blaming “soil behavior” for what was boundary behavior. Handy reminder: penetration correction card.

| Factor | Effect on penetration | What I do |

|---|---|---|

| Larger D50 | More intrusion | Upsize specimen Ø |

| Thicker wall | Less intrusion, more restraint | Choose medium, verify |

| Surface roughness | More intrusion | Smooth, re-trim surface |

| High σ₃ | More intrusion | Confirm size, apply correction |

Thin vs. Thick Membranes: How Thickness Influences Stress Measurement

Thickness changes hoop stiffness and end-friction behavior—subtle, but visible in plots.

Thick walls add radial restraint and can inflate apparent strength; thin walls keep fidelity but demand clean mounting and careful leak control.

Think of the membrane as a spring in parallel with the soil’s radial response. A thick wall increases that spring stiffness, which means at the same cell pressure the specimen expands less radially. The result: slightly higher measured deviator stress at a given axial strain and a muted dilation signal in dense sands or overconsolidated clays. Your effective stress path may show reduced excess pore pressure in CU, not because the soil changed, but because the boundary got stiffer.

A thin wall reduces this added stiffness, so pore-pressure development and volume-change trends look more “alive.” The trade-off is reliability: thin walls are unforgiving of burrs, vacuum spikes, and undersized IDs. For fine clays (D50 < 0.02 mm) at modest σ₃, I favor thin walls to protect B-values and volume fidelity. For angular sands or high σ₃, I step up to medium thickness.

Quick guardrails I use: thickness picker.

- Clays (Ø 38–50 mm): 0.30–0.35 mm (thin) for CD/CU fidelity.

- Silt/silty clay: 0.35–0.45 mm (thin–medium).

- Fine sand: 0.45–0.60 mm (medium), 0.60–0.80 mm for Ø ≥ 70 mm or high σ₃.

| Wall | Confinement bias | Pore pressure fidelity | Tear/leak risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thin | Low | High | Higher |

| Medium | Moderate | Good | Moderate |

| Thick | Higher | Lower | Lower |

Thin vs. Thick Membranes: How Thickness Influences Stress Measurement

Yes, again—because thickness also touches measurement method and corrections.

Use membrane-stiffness and penetration corrections when needed; validate with dummy runs so σ₃ and volume aren’t storytelling.

Even with the “right” wall, I ask: do my measurement paths hide a bias? If I derive deviator stress and volume change from controller data, membrane effects sneak in unless I control them. I do three simple things.

1) Dummy-cylinder check. I mount a smooth metal/polymer dummy with the same membrane and run a short consolidation under target σ₃. Any “volume change” I see isn’t soil; it’s plumbing + membrane. I subtract this baseline from real tests. Notes here: dummy workflow.

2) Thickness logging + scatter watch. Every time we change lot or wall grade, I watch the first three tests’ B-values, early v–t slopes, and the peak/critical ratios. If they shift in ways the geology can’t explain, the membrane likely did.

3) Correction discipline. For granular materials, I apply a membrane penetration correction; for stiffer walls, a small membrane stiffness correction to deviator stress (lab method sheet pinned near the frame). None of this is complicated, but it turns “I think” into “I know.”

Bottom line: thin walls maximize fidelity; medium walls buy robustness. Thick walls are for special cases—abrasive grains, very high σ₃, or custom rigs. Pick on purpose, then prove with a quick calibration so your σ₃ is what the specimen truly feels: calibration checklist.

Conclusion

Choose thickness on purpose, verify with quick calibrations, and correct small biases—then trust your σ₃ and your curves.