I’ve been asked this more than once: can unlubricated condoms1 stand in for lab membranes?

Short answer: possible in a pinch, but risky—thickness, elasticity, tolerances, and QA differences can distort triaxial data2 and increase failure rates.

Let’s unpack the trade-offs with plain, field-tested logic.

Why do some labs consider condoms as membrane substitutes?

Budgets are tight, and “it stretches like latex” sounds convincing—until tests misbehave.

Labs try condoms for cost and availability, but variability in wall thickness, sizing3, and consumer-grade QA4 often undermines repeatability5 and accuracy.

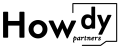

I understand the temptation. When a shipment was delayed in Ohio, a lab tech handed me a box of unlubricated condoms1 and a hopeful shrug. We actually mounted one on a 38 mm dummy cylinder. It worked—sort of. But under cell pressure, the mid-height bulge grew more than expected, and the B-value6 later drifted. The point isn’t that it never works; it’s that it rarely works predictably.

Dive deeper: where the idea makes sense—and where it breaks

The idea usually starts with three arguments: price, availability, and elastic latex. For simple demonstrations, teaching labs, or quick visual checks, a consumer product that already comes in a tubular shape looks attractive. It’s pre-formed, easy to slip over a small cylinder, and widely stocked. For noncritical demos—say, showing membrane mounting in a classroom—this can be good enough: demo-only uses.

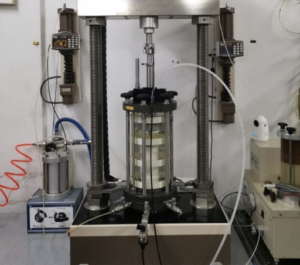

But research and commercial QA demand repeatability5. Condoms are consumer goods optimized for comfort, discrete packaging, and human-use QA, not for uniform wall thickness, tight inner-diameter (ID) matching, or traceable lot tolerances7 at the levels geotechnical tests8 expect. In triaxial work, small differences in wall thickness and pre-tension change radial stiffness9, alter volume-change readings10, and bias peak strength. Add potential powders11, coatings, or residual mold-release films (even on “unlubricated” products), and you risk compatibility issues with stones, pore lines, or adhesives.

Another practical gap: sizing3. Lab membranes are sized by precise ID ranges to fit 38 mm, 50 mm, 70–100 mm specimens with minimal folds. Consumer sizes are not calibrated for those diameters or for L/D = 2.0–2.5 geometry. Extra length and variable taper create folds that later act like bladders, faking dilation12 or compression. In short, the concept is understandable—but the hidden costs appear later in your plots: [repeatability](https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11996692/)5 checklist.

Material comparison: latex properties, thickness, and elasticity

Both are latex—but the details decide if your data is honest.

Lab membranes target narrow thickness tolerances, steady modulus, and clean surfaces; condoms vary in wall thickness, taper, and coatings, affecting stiffness, sealing, and drainage paths.

Where specs start to diverge

| Property | Lab Membrane (latex) | Unlubricated Condom |

|---|---|---|

| Wall thickness | Specified grades (e.g., 0.30–0.80 mm) with tight tolerance | Thin, often <0.10 mm; variability across length |

| ID tolerance | Sized to specimen Ø (snug fit) | Consumer sizing3; not matched to 38/50/70 mm |

| Modulus/elasticity | Tuned for stable radial response | Optimized for comfort, not uniform radial stiffness9 |

| Surface finish | Clean, powder-free; optional transparent | May include residual powder/film; clarity varies |

| Batch traceability | Lot QA available | Limited or consumer-centric QA info |

What that means in practice: thin, variable walls can increase radial compliance, cause micro-bulging13, and skew q–ε curves. Residual films can interfere with sealing or pore-pressure lines.

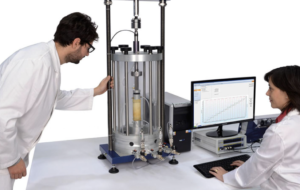

Dive deeper: thickness tolerance and the “membrane system”

In triaxial testing, the membrane isn’t invisible; it’s part of the system stiffness. A membrane that’s too thin or uneven shifts how radial strains develop. With consumer condoms, wall thickness can vary along the length due to taper and tip design, so mid-height may behave differently from the ends. This becomes noticeable in CU and CD tests. In CU, where pore pressure behavior is central, extra radial compliance can damp or distort excess pore pressure build-up, nudging your effective stress path14. In CD, folds and variable tension alter volume-change readings, making dilation12 appear muted or sporadic.

Another marker is surface finish15. Lab membranes are typically powder-free and use packaging that avoids surface micro-damage. Some consumer products rely on minimal powders11 or internal treatments to aid donning; even “unlubricated” items can retain trace films. Those traces attract fine particles, complicate sealing at caps, and can leave paths for slow leaks. Transparent lab membranes (one of my favorites) let me visually confirm bubbles and wrinkles during mounting; most consumer alternatives are not designed for optical clarity against a black specimen, making it harder to spot early problems: membrane clarity notes.

Finally, traceability matters. When a batch of lab membranes runs slightly thicker, I can adjust. With consumer goods, the next box—even from the same brand—may feel different. In data work, that unpredictability is expensive.

Practical limitations in triaxial testing performance

Mounting looks fine at first; problems appear during saturation, consolidation, and late-stage shear.

Expect higher leak risk, fold-induced artifacts, unstable B-value6s, and distorted volume-change curves; repeatability5 across specimens and boxes is the main casualty.

What goes wrong (and where you’ll see it)

- Saturation/B-check: tiny pinholes or poor sealing keep B < 0.95.

- Consolidation: variable pre-tension changes volumetric response and rate.

- Shear: folds act as micro-bladders, faking dilation12; bulging shifts peak strength.

- Repeatability: box-to-box variability widens scatter in φ′ and c′.

| Stage | Failure mode | Symptom | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mounting | Fold/overstretch | Wrinkles | Noisy volume curve |

| Saturation | Micro-leak | Low B-value6 | Unreliable u-excess |

| Consolidation | Variable wall stiffness | Drift in v–t | Misread compressibility |

| Shear | Mid-height bulge | Early softening | Lower stiffness / altered peak |

Dive deeper: where artifacts sneak into your plots

The triaxial plot is honest, but only if the setup is. Artifacts show up as small clues: a B-value6 that refuses to climb; a “breathing” volume curve in CD; or a stress–strain curve that softens early without a fabric reason. Condoms increase the likelihood of those artifacts because membrane geometry and material finish weren’t tailored for cylindrical soil cores. Extra length creates loose folds; taper and rolled ends change pre-tension at the caps. When the cell pressurizes, those folds expand or shift, acting like tiny reservoirs that either store or release water independently of the soil, giving false dilation12/compression signals.

In CU tests, even a small leak reduces the measured excess pore pressure, sliding your effective stress path14 and, ultimately, your derived φ′ and c′. You might be tempted to raise back-pressure time, but the underlying issue is sealing, not patience. In UU tests, where speed rules, the fragility of very thin walls shows up as mid-height splits at higher deviator stresses.

Could careful mounting mitigate some issues? Somewhat: a membrane stretcher, strict deburring, and very gentle vacuum help. But the basic mismatch of ID tolerance, thickness distribution, and batch control remains. For critical work, that mismatch is the difference between data you defend and data you doubt: artifact spotting guide.

Cost vs reliability: when “cheap” alternatives become expensive

Time lost to reruns costs more than any discount on consumables.

Initial savings vanish with extra mounting time, leak checks, failed B-value6s, and scattered results; lab-grade membranes win on total cost of quality16.

Simple math I show buyers

| Item | Condom Substitute | Lab Membrane |

|---|---|---|

| Unit price | Low | Moderate |

| Mounting time | Higher (fold control) | Lower (size-matched) |

| Failure/re-run rate | Higher | Lower |

| Data scatter | Wider | Tighter |

| Total cost per valid test | Often higher | Predictable, lower scatter |

A few dollars saved on consumables can become hours of technician time and lost machine slots. Worse, you lose confidence in the curves.

Dive deeper: total cost of quality16 in geotech labs

When I evaluate consumables, I don’t stop at unit price. I use a simple TCQ (Total Cost of Quality) lens: (material) + (time) + (rework) + (risk). On paper, a condom looks inexpensive. In practice, your time balloons: more effort to control folds, more bubble tests, more remounts. Rework grows too—B-value6s below 0.95, strange volume curves, and early shear anomalies push you to repeat tests. And risk isn’t abstract; it’s the chance you publish or approve designs off skewed parameters.

If your lab runs student demos or very rough screening, substitutes can have a place—as long as you label those results non-design17 and keep them out of formal reports. For all design-grade work (foundation, slope, embankment), I pick membranes with documented thickness tolerance, ID matching, and traceability. Consistency narrows your φ′ / c′ scatter; that pays back quickly in fewer repeats and faster decisions.

One honest middle ground is to keep two membrane thicknesses per diameter—thin for clays and CD fidelity, thicker for sands and high σ₃. If transparency helps your team catch wrinkles faster (it does for mine), choose transparent lab membranes18 and standardize a calm mounting SOP: [SOP template](https://www.ehs.harvard.edu/lab-standard-operating-procedure-templates)19. The goal isn’t fancy—it’s boring reliability that lets you trust every point on your plot.

Conclusion

For demos, maybe. For real data, use lab membranes—your time and curves are worth it.

-

Explore the pros and cons of using unlubricated condoms as lab membranes for better understanding. ↩ ↩

-

Learn about triaxial data and its importance in geotechnical testing for accurate results. ↩

-

Discover the factors that influence sizing for lab membranes and their importance. ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Understand the implications of consumer-grade QA on testing accuracy and reliability. ↩

-

Discover why repeatability is crucial for reliable lab results and how to achieve it. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Explore the meaning of B-value and its relevance in geotechnical testing. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Understand the significance of traceable lot tolerances in ensuring material quality. ↩

-

Learn about various geotechnical tests and their roles in engineering projects. ↩

-

Gain insights into radial stiffness and its impact on testing outcomes. ↩ ↩

-

Explore the methods of measuring volume-change readings in geotechnical testing. ↩

-

Learn about the effects of powders on lab testing and how they can impact results. ↩ ↩

-

Discover the concept of dilation and its significance in geotechnical testing. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Learn about micro-bulging and its effects on test results in geotechnical applications. ↩

-

Discover the concept of effective stress path and its relevance in soil mechanics. ↩ ↩

-

Understand the impact of surface finish on the performance of lab membranes. ↩

-

Explore the total cost of quality and its implications for lab operations. ↩ ↩

-

Understand the term non-design and its implications for lab testing results. ↩

-

Learn about the advantages of transparent lab membranes for better visibility during tests. ↩

-

Explore the importance of SOP templates for standardizing lab procedures. ↩